Snakes are: COOL!!!

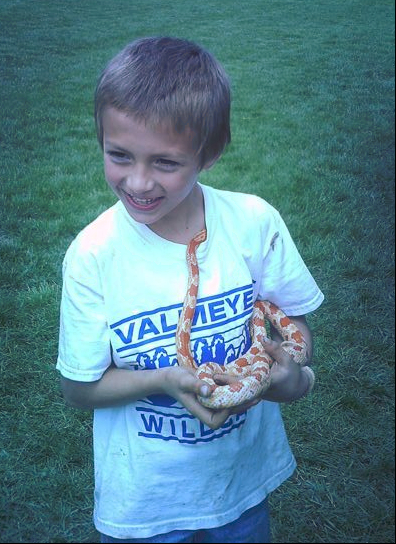

Irresistible. Couldn’t be ignored. Had to look. Must – oh my! – even be touched.

“Not slimy” – the first reaction – turned into the next observation: “This is so COOL,” accompanied by a feeling of accomplishment made even more pleasant by the admiring glances of onlookers. Everybody wanted to touch a snake.

The live animal demonstrations, including TreeHouse Wildlife Center’s American Kestrel and Barn Owl, the turtles shown by Simon Bade and the snakes brought by Hugh Gilbert, were the most crowded exhibits at Festival of the Bluffs, as attendees flocked to get a better look and learn about a few of our wildlife neighbors. Hugh and his ever-patient snakes, which agreeably coiled, wound and twisted round the wrists, arms and necks of all comers, taught lessons in the reality of wildlife and countered some mythic fears.

“Ophidiophobia” — fear of snakes — is common; yet, in terms of danger to humans, snakes present miniscule actual danger, far less than, for example, getting in one’s car and driving to a destination. Humans pose far greater threats to snakes for unfortunately people kill many snakes each year, sometimes in the belief that killing a snake – any snake – is the right thing to do. Timber Rattlesnakes are among the most feared, but not truly fearsome, wildlife neighbors of our area.

Fear of rattlesnakes and the willingness of many people to kill them probably is as much a product of Hollywood Western-genre movie and television productions as deep-seated cultural traditions. In our part of the nation, the chance of being struck by lightening is statistically more likely than the risk of being bitten by a venomous snake. Snakebites from venomous species in Illinois are so rare that no public health statistical records are available.

In the U.S. overall, an average of about 7,000 venomous snakebites are reported annually, according to the Palm Beach, Florida, Herpetological Society. About 3,000 of these cases occur because the person was handling or molesting the snake. With only 15 fatalities per year, the survival rate is very high – upwards of 99.8 percent. These statistics include bites from any of the 20 venomous species that occur naturally in the U.S., as well as bites from non-native species imported and/or captive-bred for the pet trade. About half of all bites were “dry,” that is, no venom at all was injected.

The lack of venom during a strike for defense actually is a hallmark of the pit viper snakes in general and of rattlesnakes in particular. Just like many of us, these snakes hate to waste their resources!

The action of injecting venom is voluntary and frequently is not done when the snake is protecting itself. Venom is used to stun and kill prey and then acts as a pre-digestant, helping the snake absorb nutrients from its meal.

All four of the venomous snakes found in Illinois are members of the “pit viper” grouping. Of the four species, Timber Rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus) and Copperhead (Agkistrodon controtrix) are found in our area; Cottonmouth (Agkistrodon piscivorus) is considered extirpated in our area, since no records occur since 1980, but still lives in undisturbed habitats in southernmost Illinois; and Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus) never occurred in our area, and is increasingly rare in the northern-to-central/south counties that once made up its range. The Timber Rattlesnake is classified as threatened and the Massassauga is endangered in Illinois.

Pit vipers are so named for the heat-sensing organs that are arranged on the upper lips of the jaws. These highly sensitive structures can detect a temperature change of less than 0.05 degrees Celsius (or less than one-tenth of a degree on the

Fahrenheit scale). Because the heat-sensing pits are located on both sides of the head, pit vipers have a bilateral system, enabling them to locate, orient on, and strike prey based on temperature cues alone. Pit vipers also possess another form of sensing which enables them to track their prey and to orient throughout their territory. The Jacobson’s organ is located in the roof of the mouth. It is a chemical sensing system, connected directly to the brain, and receives data from a snake’s consistently flickering tongue, in a sense allowing the snake to “smell” its way through the world. Such naturally superior arrangements – comparable in a weak sense to our clumsy use of night-vision goggles – allow these snakes to hunt efficiently at night or to lay in wait for prey to enter a dark crevice.

Pit vipers are highly effective hunters and, as Scott Ballard noted in a 1999 article for Illinois Audubon Magazine, their methodology is familiar to any human deer hunter:

“Just as a hunter uses a weapon to inject a slug or arrow into a deer to immobilize it, the pit viper uses its fangs to inject venom to immobilize a small mammal. As the hunter tracks an injured deer to where it lies, the pit viper uses its tongue and Jacobson’s organ….to track the trail left by its prey until the prey is found. The hunter waits until the deer is dead to field-dress it, and the pit viper waits until its prey is dead to eat it.”

Just as successful human hunters patiently wait for their prey to appear, so do both Timber Rattlesnakes and Copperheads, our area’s only – though still rarely – encountered pit vipers. This very technique, however, often causes humans to mistake the snake’s intention and misunderstand the stillness as a form of aggressive “standing its ground.” Neither species, however, is aggressive. Both species rely on their coloration as a disguise and a means of blending in to the background – like a human hunter’s camouflage gear – as they wait for a meal to cross their path.

This is not to downplay the seriousness of a venomous snakebite; such an occurrence is a medical emergency and immediate treatment should be sought. The risk of such an incidence is very rare, less than the chance of a lightening strike. Risk, however, also can be increased by our response; more than 40% of venomous snakebites are the result of mishandling and, even, molesting the snake. A snake that is not cornered, not stepped on and not picked up generally will not bite.

The best response to seeing a pit viper – or other snake or any wildlife of our still natural resource-rich area — is respect, not revulsion. The snake will not attack – a human is only too obviously NOT food to their extraordinary senses – but the snake will continue to rely on its cryptic camouflaged coloration to protect itself from the danger humans pose. Leaving the snake – and all wildlife — unmolested and simply walking away is the respectful choice.

And, if you’ve ever railed against mice and the wasteful damage they do, you might think to whisper “thanks,” as you walk away from and leave unmolested any snake you encounter. Our larger snakes each can eat up to nine pounds of mice in a year. Small snakes, like the Ring-Necked Snake (Diodophus punctatus), largely feed on insect pests.

While all the snakes contribute to our ease through their consumption of pests, and pit vipers use hunting methodologies we’d recognize and applaud for efficacy, and Timber Rattlesnakes are parsimonious with their venom, this species shares yet one more characteristic celebrated among human residents of our bluff lands.

Timber Rattlesnakes are multi-generational residents of their particular homelands. Unlike us, however, these snakes cannot choose to stay home or emigrate elsewhere. Instead, they are obligated to remain within a distinct home area and, if they ever are moved even a relatively small distance away, find such relocation a death sentence.

This tightly constricted geographic limit is a result of the finely tuned chemical sensing mechanism, the Jacobson’s organ that works so well in processing chemical cues. Each Timber Rattlesnakes follow chemical “scent” trails on their annual journey to and from their denning sites. Young rattlesnakes are born live close to the den site and follow chemical cues left by their mother to return to the den. The summer hunt for food and for mates may take a snake as far as two miles from the den site. As winter approaches, each snake returns to the specific den used for generations of its ancestors. The destruction of a den site destroys generations of snakes. Removal of a snake from its homeland results in death as the individual can find no scent cues, no way to orient, and no way to get back home.

The strong forces of the obligatory generational home meant that many Timber Rattlesnakes shared winter dens. And, indeed, winter dens containing hundreds of rattlesnakes once were known in Illinois. But wanton destruction by those intent on killing the snakes and those who sought to collect either live animals or trophy rattles greatly reduced or even eliminated these populations. Changes in land cover and use, and loss of forested habitats also have put great downward pressure on the species. Timber Rattlesnakes once lived in 36 counties in Illinois, but now are found in only 21, and, of these, the species is in decline except in areas of intact habitat.

Our bluff lands of Monroe and Randolph Counties still contain populations of Timber

Scott Ballard, Illinois Department of Natural Resources. This rattlesnake has had nail polish painted onto a row of rattles an aid in future identification should IDNR Heritage Biologists see this snake again.

Rattlesnakes. The population numbers – based on census from road killed specimens and reports of sightings – indicate continued declines, so much so that our populations may be considered “relict,” a strong indication that long-term viability of this species in our area is no longer possible.

While we still may speak of Timber Rattlesnakes as fellow residents of our area, Clifftop and the Monroe County University of Illinois Extension Service are co-hosting a seminar on Timber Rattlesnakes. Scott Ballard, IDNR Heritage Biologist and Herpetologist will focus on the natural history of Timber Rattlesnakes.

Clifftop, a local nonprofit organization, is focused on preserving and protecting area bluff lands.

Versions of this article appeared in the July 1 2009 edition of the Suburban Journals Clarion Enterprise and in the July 3 2009 edition of the Monroe County Independent.

© 2009 all content rights reserved, Clifftop NFP.

Comments are currently closed.