New Lessons from Smokey the Bear: Renewing the Landscape with Fire

The Southwestern wire services and blogs this week have relayed a story about

an American icon who may be nearing his end.

Smokey Bear is reported to be in terminal decline. Retired to an assisted living facility near Truth or Consequences, NM, he apparently is suffering from a host of maladies.

Smokey’s meteoric rise to national acceptance, his decades-long hold on our fearful imaginations, and the recent modification of his lifelong message all serve to remind us that ground truth can be illusive and there always can be unintended consequences.

Smokey Bear was born in 1924 or 1925 in the Elk Mountains of New Mexico. His grandfather, affectionately known to the greater family as “Papa Bear,” instructed young Smokey and helped him become an expert woodsman. Papa Bear drew on the extensive woods lore he learned as a youth and which his clan, originally based in the great forests of the Eastern U.S., had passed down from generation to generation. Papa Bear and his mate — fondly recalled in later years by Smokey as “Mama Bear” — did their best to keep tradition alive.

During stormy nights, with the family gathered together in the den, Papa and Mama Bear often would tell of life “back East,” sometimes speaking of storms, and often remembering the earth-hugging fires of fall and spring, some set by lightening, others by humans. Fire helped clear the land of brush and made passage through the great woods quick and easy for their kind. But most often they recounted their memories of the grand woods of the East: great towering oaks and hickories stretching to the sky and sun-dappled forest floors dotted with wildflowers and filled, each season in turn, with wholesome foods including berries, nuts and acorns, mushrooms, and healthy game populations.

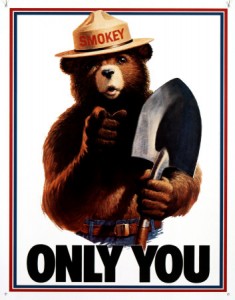

Like many a youth before him, young Smokey found the attractions outside his simple forest home too tempting to ignore and spent several years carousing in and around local towns. But one evening in 1942, while raiding a dumpster at a drive-in theater at Las Cruces, Smokey saw Walt Disney’s “Bambi” and experienced an epiphany. Transfixed by the movie, Smokey rededicated his life and soon began traveling throughout the Southwest preaching to one and all: “Only you can prevent forest fires.”

His pronouncement caught the eye of local Federal officials, who invited him to Washington D.C. for a series of highly confidential meetings. In the years leading up to World War II, terrible fires had occurred in the South and West. And, though at the time a closely held secret, shortly after the declaration of war, very large balloons, capable of wafting along on the jet stream, had been released by the Japanese. These floating weapons, carrying explosives and incendiary materials, were an attempt to wreak havoc and to destroy timber reserves in the Pacific Northwest.

The Federal government, strapped for resources in time of war, was deeply concerned about national response capabilities for natural disasters. The Wartime Advisory Board believed they had found in Smokey’s simple statement a message that would resonate with the American people.

Smokey was immediately offered a job.

When the war was over, Smokey became the spokesbear for the U.S. Forest Service, and rapidly became even more popular, even a celebrity.

Smokey Bear’s “all fire is bad” mindset held sway for several generations of Americans. But, like many Federal bureaucrats, Smokey remained behind a desk in Washington and failed to notice changes in our nation’s forests. The necessity of always staying “on message” — and Smokey always had only one — made him lose sight of the subtleties and nuances of nature and concentrate only on the ironclad policies that had been created.

Smokey forgot Papa and Mama Bear’s stories of small and frequent fires that kept forests healthy, and clear of brush so that the forest floor still received plenty of sunshine to grow wildflowers and encourage seedling oaks and hickories into stout growth. He forgot the little wildfires that cleared the forest floor of debris and

burned minor fuels before they accumulated into large stands of kindling. He didn’t notice the vast buildup of dead fuel collecting in our woodlands. He didn’t comprehend the importance of the movement of suburbs and housing developments ever deeper into the woods.

Smokey Bear never actually visited our blufflands. However, just like the great forests of the East, our native oaks and hickories need periodic fire to prosper. Native Americans routinely had set fire to our woods and grasslands to keep them productive for hunting and agriculture. The early Euro-American settlers continued the practice, burning the woods two or three times each decade. Our great-grandfathers and grandfathers burned woodlots and pastures in the bluffs into the 1950s.

The cessation of periodic fire in our bluffs has had transformative and deleterious impacts over the last fifty years.

Our canopy-dominant oaks and hickories are now mostly mature or over-mature trees. Shorter-lived hackberries and persimmons, which share the canopy, mostly are entering extreme old-age decline and senescence. None of these native trees are regenerating themselves very well anymore.

Instead, fire-intolerant native sugar maples and nonnative Tree-of-Heaven are taking over the mid-story of our woodlands. And, nonnative fire-intolerant bush honeysuckle shrubs are taking over the understory. Taken together, these invasives are shading out new oak-hickory regeneration. It simply is too shady for acorn and nut seedlings to sprout and grow.

In time, largely because of the lack of fire, our oak-hickory forest will be no more. Then, our acorn and nut-dependent deer, turkey, quail and a host of non-game critters will have to move on. Our dappled-light loving, open-woods dependent wildflowers and mushrooms will go away. And, our open trails and scenic swales will be a thing of the past.

Recognizing these negative impacts to our forests, in recent decades, science-based land management practices have readopted the age-old use of fire as an important tool to revitalize and maintain ecosystems like our blufflands.

It is called prescribed or controlled burning. It’s called “prescribed” in the same sense as a pharmaceutical prescription, a medicine to cure ills on the landscape. It is called “controlled” because every effort — from detailed planning through execution and mop-up — is carefully designed to control and contain the inherent danger of fire.

In November, after leafdrop, through late March, before green-up begins, Illinois Department of Natural Resources professionals will conduct prescribed burns on select, state-managed woodlots and prairies in the bluffs. They will do so in accordance with Illinois’ new Prescribed Burn Act, Public Law 095-0108, enacted in August, 2007. The new law also provides authorizations and guidelines for private landowners to conduct prescribed burns on their own property.

With every prescribed burn, planning and preparations are paramount. Burn units are carefully demarcated; firelines are carefully constructed; and potentially troublesome fuel sources are isolated.

A trained and certified Burn Boss is in charge of each burn. A written Burn Management Plan is developed for each burn. And, County Sheriffs’ Dispatchers and the jurisdictional Volunteer Fire Departments are notified before each burn.

Each prescribed burn is conducted only under specific weather conditions, and if the weather is uncooperative the planned burn is canceled. Wind speed and direction, air temperature and humidity are key factors in influencing fire behavior and the trajectory of smoke.

A controlled burn, beyond benefiting the woodlands, makes the forest safer from risk of out-of-control wildfire. Potentially highly flammable brush, accumulated and dried for years, could result in disastrous — and uncontrolled — wildfires. Despite the discomfort of smoke from a controlled burn, controlling smoke now is better than uncontrolled smoke, from an unwanted fire, later.

Sooty the Bruin, Smokey Bear’s great grand nephew who is a certified Burn

Boss, and, perchance, the new poster bear for healthy forests, knows full well that the best way to fight fire — and maintain our natural blufflands — is with fire.

Clifftop, a local nonprofit organization, is focused on preserving and protecting area bluff lands.

Versions of this article appeared in the October 1 2008 edition of the Monroe County Clarion and in the March 5 2010 edition of the Monroe County Independent.

© 2008 all content rights reserved, Clifftop NFP.

Comments are currently closed.