Thousands of Sinkholes, Hundreds of Caves, Dozens of Rare Species…. Recent Discoveries and New Data About Our Karst Landscapes

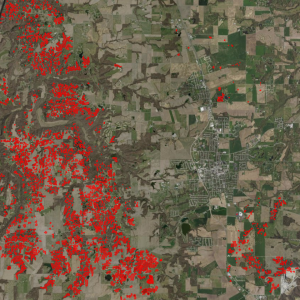

Sinkholes are the most obvious karst landscape feature in southwestern Illinois. Using GIS tools and LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) images, over 15,000 sinkholes have been mapped in the area of Monroe, Randolph, and St. Clair Counties known as the Sinkhole Plain. Monroe County recently launched an interactive map showing sinkhole distribution in the county (check it out at https://monroecountyil.maps.arcgis.com/home/index.html). At left is a screenshot from the map website showing sinkhole density in the Waterloo area. These depressions form in places where the thick layer of loess soil erodes into crevices and caves in the limestone bedrock, creating voids in the soil that eventually collapse. Some sinkholes plug with soil and hold water, creating semi-permanent ponds. Sinkhole ponds are important habitat for amphibians, dragonflies, waterfowl, and scores of other aquatic creatures. Although a sinkhole pond may support a lively sport fishery, fishless ponds have greater ecological benefits, especially as amphibian breeding sites.

Many sinkholes remain open to water flow and become direct conduits that focus surface runoff into the karst groundwater systems. This direct connection makes groundwater and cave streams quite vulnerable to contamination and pollution. A 2014 study conducted by scientists at the University of Illinois Prairie Research Institute, with support from Clifftop and Southwestern Illinois College, analyzed water from 10 caves and springs in the Sinkhole Plain and discovered widespread presence of fecal coliform bacteria and chemicals from pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs), like the lipid-lowering drug Gemfibrozil and an antibacterial chemical common in soaps, Triclocarban. Stemler Cave and its resurgence point, Sparrow Spring, had the highest concentrations of PPCPs: 7 of the 15 chemicals tested for were detected. The study suggests septic systems (poorly maintained home aeration systems and faulty leech fields) are the source of the PPCPs and some of the bacteria that are contaminating the groundwater systems in our area.

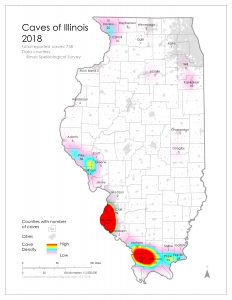

While sinkholes are obvious, caves are by definition subterranean and therefore are hidden from our everyday view. So, most residents would underestimate the number of caves known from the area. According to a 2018 summary by the Illinois Speleological Survey, more than 300 caves are reported from the Sinkhole Plain, with 75% of the caves occurring in Monroe County. Many of these caves are small “bellycrawls” but several quite large caves are found in the area, including Fogelpole Cave. A visit to Clifftop’s Paul Wightman Subterranean Nature Preserve, 3325 G Road, Fults, provides a chance to hike on well-maintained trails that traverse the landscape above a portion of the cave and learn about karst from the excellent interpretive signs. With over 15 miles of mapped passage, Fogelpole is currently ranked the 54th longest cave in the United States and is Illinois’ largest and most biodiverse cave with at least 15 totally cave adapted invertebrate species present. There are almost 50 cave dwelling invertebrate species considered “globally rare” in Sinkhole Plain caves as well as several threatened and endangered cave species. There are even newly discovered cave animals that have not yet been named and formally described by scientists. Some of these rare species are limited to just one cave.

The Enigmatic Cavesnail is a state endangered species. The only Illinois population is found in Stemler Cave. Like other totally cave adapted species, this snail is eyeless and void of pigmentation. Research at Southwestern Illinois College has provided some interesting clues about the life history of this little snail. Female snails attach individual eggs to the underside of rocks in the cave stream. The embryos are only 0.75mm at hatching (3/100 of an inch) but take a surprisingly long time to develop; an average of 72 days of embryonic development. Hatchling snails take at least 5.5 months to grow to the minimum adult size of 2mm. Most cave adapted species are slow growing and long lived. Nutrients that naturally wash into the cave allow biofilms to grow on rocks in the stream bed. Snails and other cave animals graze on the biofilms. Septic contamination and other forms of excess nutrient runoff from the surface can fuel heavy bacterial growth that reduce the oxygen content of the water and provides enough extra food to allow non-cave species to make a living in caves, placing competition pressure on the cavesnail and other rare “troglobite” species. While some readers may not be concerned about the survival of this tiny snail, its fate is tied to the overall health of the cave ecosystem and the entire groundwater system.

CLIFFTOP, a local nonprofit organization, is focused on preserving and protecting area blufflands.

A version of this article appeared in the November 1, 2019 edition of the Monroe County Independent

©2019 all content rights reserved Clifftop NFP

Comments are currently closed.