Fungus Among Us: Valuable Player in Our Ecosystem

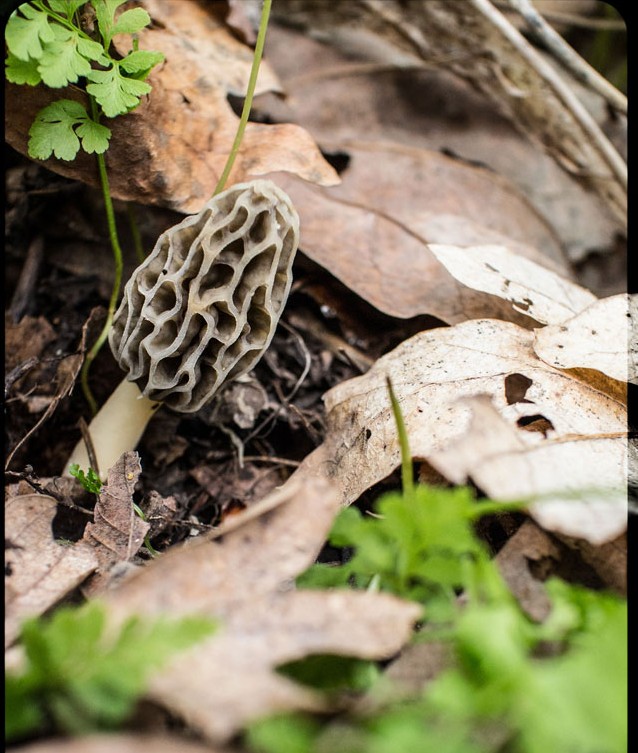

The fungus among us are quite literally everywhere. They grow under – and even in — our very noses. When scrambling about our woodlands in search of morels, take into account that the normal, healthy human mouth hosts about 300 species of beneficial fungi.

Fungi are members of their own biological kingdom and are neither plant nor animal. They grow and fruit much the way plants do, but lack roots, stems, leaves, flowers and seeds. They also lack chlorophyll and do not feed themselves through photosynthesis. Like animals, fungi acquire food by secreting digestive enzymes and absorbing the resulting dissolved molecules. Thus fungi feed themselves by absorbing nutrients from their surroundings, and, as a result play an essential role in the decomposition of organic matter.

About 100,000 species of fungi have been identified by science and it is estimated that perhaps a million additional species remain to be identified. Fungi are broadly categorized as algal blights, yeasts, molds, rusts, smuts and mushrooms.

While fungi can cause a variety of crop, animal, and human diseases, they are also critically important to nutrient recycling. Without fungi, decomposition comes to a halt. Fungi also help fight infectious diseases in plants, animals and mankind. They are used as leavening agents for breads, fermentation agents, the development of antibiotics and pesticides, and, of course, for human food.

Nothing seems more magical and fairytale-like than searching for mushrooms. With over 3,000 species of mushrooms in Illinois, the ancient tradition continues, spurred on by luring, common mushroom names like Scarlet Elf Cup, Orange Fairy Cup, Elfin Saddle and Fairy Ring.

But we should all be wary that all mushrooms aren’t good to eat. As the German proverb states, “all mushrooms are edible, but some only once.” Local names for mushrooms such as Dead-Man’s Fingers, Devil’s Urn, Witch’s Butter, Deathcaps, Many Warts, Weeping Widows’, Poison Pie and Sickener serve as a reminder that many mushrooms are poisonous.

The perplexing thing about forefathers’ common names for mushrooms is that they don’t tell us the whole story. You would think our forests offer a smorgasbord, a cornucopia, of good eating, with a menu of Pancake Cup, Doughnut, Tooth Jelly, Cauliflower Coral, Pigs’ Ears, Turkeytail, Beefsteak, Chicken-of-the-Woods, Honey, Oyster, Onion Stem, and Red-Wine Milkcups just waiting to be picked. The problem is half of the selection is toxic if eaten.

Mushrooms are a particular type of fungus. The item we call a mushroom is the fruiting body, rising out of the large branching, but filmy structure called a hypha, from the Greek word for ‘web.’ Fungal hyphae are the means of growth, the structures that secrete enzymes and take up nutrients. The fleshy fruiting body – what we call a mushroom – is called a sporocarp and produces spores, the reproductive units, produced without sexual fusion, and that generally are visible only through a microscope.

Mushrooms are divided into two major types, or phylums, based on spore production and appearance. In the Ascomycota division, commonly called sac fungi, spores are contained within a sack-like structure. The group contains over 64,000 species, and includes the morels, false morels, cup fungi, earth tongues, tubers and truffles. This large Ascomycota grouping includes both brewer’s and baker’s yeasts and various penicillin species, but also contains a number of plant-disease producing species such as apple scab and powdery mildews.

The other major grouping of the “higher fungi” is the Basidiomycota, and, in this grouping, spores are produced on the surface of cells. Among the nearly 32,000 species of this large grouping, are the familiar cap-topped mushrooms, as well as puffballs, boletes, chanterelles, and stinkhorns.

All these fungi types break down organic matter as a means of growth and eventual reproduction. Many live on dead plant material, like leaves, twigs or fallen logs, but some types also can break down collagen, the structural protein of animal connective tissue, and others feed on keratins, the protein that forms skin and nails. Very specialized fungi in the Ascomycota phylum can feed on paint, while members of another genus specialize in resins and kerosene, and in natural settings are found in association with certain pine trees, but also take advantage of human-created settings and can grow in fuel lines and tanks.

While the fungus among us seemingly can exploit an endless variety of nutrient sources, we directly consume only a very small number of mushroom types. A few rare types, such as truffles, are among the world’s most expensive foods. The ‘guardians’ of Monroe County morel patches – perhaps our area’s most secretive society – look forward to springtime searches for treasures and bragging rights to first found, most found, and best taste. Those knowledgeable about mushrooms through the seasons may continue their treasure hunts for chanterelles in summer, black trumpets, shaggy manes, and chicken of the woods in the fall, and oysters as late as the end of October. A diversity of tastes and, so long as the choice was not a mistake of the “eat that only once” poisonous varieties, a feast through the seasons from the wondrous web of biodiversity.

CLIFFTOP, a local nonprofit organization, is focused on preserving and protecting area bluff lands.

A version of this article appeared in the 4 September 2015 edition of the Monroe County Independent.

© 2015 all content rights reserved Clifftop NFP

Comments are currently closed.