Rivers Run Under Us: Karst Topography of Porous Limestone

Rivers run under us. An amazing underworld lies beneath our bluff lands. Our region’s distinctive geologic history literally laid the groundwork for the area’s unique subterranean landscape, a rugged, yet beautiful topography called “karst.”

Beginning about one billion years ago, earth’s first continents rifted and began migrating to the equator. What was to become Illinois drifted along for the ride, a part of the North American plate.

From 360 to about 300 million years ago, our part of the state was covered by a vast, shallow and tropical inland sea. To the south, the shoal waters opened to the deeper ocean, with dry land areas found only far to the north of what eventually would be Southwestern Illinois.

Our landforms — above and below ground level — were the result of the slow accumulation of sedimentary rock. Shallow water marine organisms built colonies from the sea floor up, each generation leaving their skeletal structures as new foundation platforms for the next inhabitants. In addition, the shells of marine animals accumulated on the sea floor. And, rivers that flowed into the shallow sea added mineral sediments that had dissolved in the fresh water as it coursed across exposed rock surfaces in the dry land areas. These ingredients — warm shallow waters teaming with coral-making and shelled creatures and the constant replenishment of mineral sediments — combined with time and the simple pressure of accumulated weight created layered sedimentary limestone rock.

By 144 million years ago, continental migration resulted in Illinois resting where it is today. The vast sea then reached inland only so far as about modern-day Cairo. Monroe County was not so very high in elevation, but was dry. The marine legacy left us perched over 500 to 2500 feet of underlying limestone bedrock, filled with numerous, fossilized marine organisms, now easily viewed as proof of our maritime heritage.

From 1.6 million through 10,000 years ago, Illinois and much of North America underwent several periods of glaciation — the Ice Ages. Most of the state was repeatedly covered by massive blankets of ice. The glaciers carved out and smoothed the flatter land forms now typical of the Prairie State.

The glaciers, however, stopped on the eastern fringes of our bluff lands. The bluff land corridor was not subjected to the scouring, smoothing and flattening action of direct glaciation. Because of this, our land remained slightly higher in elevation than glaciated areas to the east and so our area is known as the Salem Plateau, a geographic extension of the also unglaciated Ozark region of Missouri.

This geologic backdrop set the stage for the karstification of our bluff lands. The thickly layered, but highly water-soluble and thus easily dissolvable limestone bedrock was (and is) mantled by a water-permeable topsoil. With the addition of slightly acidic water, our karst landscape was quickly created.

Rain in our area always is slightly acidic due to droplet formation around micro-particles of acidic soil and dust and because of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Our topsoils, slowly accumulated layers of pulverized rock dust blown to our area from winds howling down from the glaciers, are relatively thin and allow rain water to quickly pass through to the limestone bedrock. Rainwater percolating through our soil becomes even more acidic because of decayed vegetation. The chemical reaction between limestone and slightly acidic rainwater creates a weak solution of carbolic acid that helps to dissolve the limestone. Cracks and planes within the limestone bedding allowed conduits to form within the underlying layers. In time, conduits enlarged, some collapsed and, in a process that continues, several geological features came to characterize our karst terrain.

Dozens of springs, scores of caves — big and small — more than in any other county in Illinois, and nearly 15,000 sinkholes can be found in Monroe and southernmost St. Clair counties. It is a little known fact that Monroe County is home to the largest cave system in Illinois and the 52nd longest cave in the United States. Fogelpole Cave, near Renault, boasts over 15 miles of mapped humanly accessible tributaries and passageways and has ceiling heights of over 60 feet in spots along the main passage. Fogelpole Cave has never been open to the public and only scientific researchers are permitted in the cave, which is carefully controlled through an entrance owned by the Illinois Department of Natural Resources.

As a result, the undisturbed Fogelpole Cave system is pristine, boasting significant, fossilized paleontological materials from the Pleistocene Era, about 36,000 years ago. These include now-extinct species of ground sloth, muskox, a giant armadillo and an early horse species. Today the cave is home to two federally listed cave-dwelling species and a dozen insect and crustacean species found nowhere else on earth.

Our karst bluff lands also host a handful of “sinking streams,” which flow along the surface, disappear, and then reappear some distance later. There is no abracadabra to these streams: if we were able to see a cross section of the earth we would see the waters simply flowing — via gravity — to their lowest point, which, because of karst geology, is through a conduit in the limestone bedrock that remains underground.

The caves, springs, Houdini-like streams and sinkholes all are testimony to the cooperative nature of limestone in amplifying the trajectory and speed of water moving into our groundwater basins.

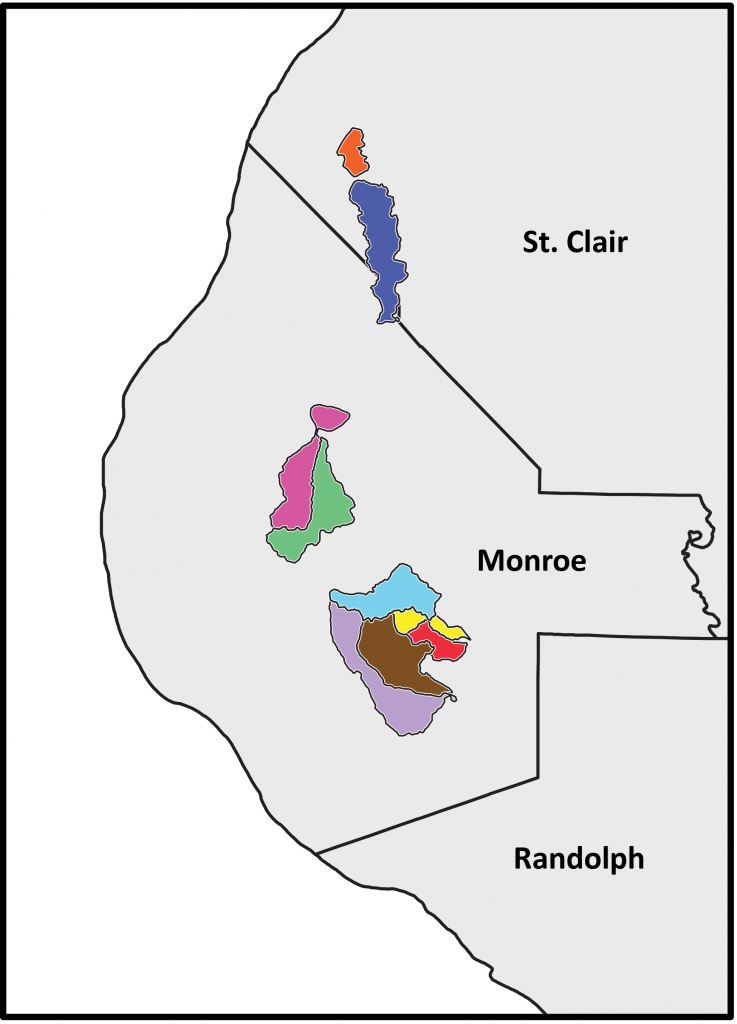

Major groundwater recharge areas on the Salem Plateau. Map courtesy Steve Taylor, Illinois Natural History Survey.

These basins are organized into distinctly different recharge, or groundwater replenishment, areas. Groundwater is funneled through conduits and caves, seeps in through sinkholes, but, with few exceptions, always remains within its given basin. It sometimes flows in directions which may be counterintuitive when compared with surface streams. This groundwater eventually emerges as a spring flowing into a surface creek, which then flows out of its basin to the Mississippi or Kaskaskia rivers. There are ten major recharge basins which have been carefully mapped in Monroe County and one basin shared with St. Clair County. These recharge basins range in size from 400 acres to over 17,000 acres, and nearly 20% of all of Monroe County’s surface acreage contributes groundwater flow into these major recharge basins. Many other, smaller, recharge basins exist throughout the two-county area, but have not been well-studied.

In our area, groundwater movement can be complex, with water flowing in the opposite direction of surface flow, sometimes even crossing obvious drainage divides to emerge in springs of neighboring drainage basins. The well-developed karst system in Monroe and St. Clair counties allows for rapid transport of suface water into the shallow groundwater which flows rapidly through conduits in the ancient limestone bedrock. In contrast, in areas without karst geology, water moves slowly from the surface into groundwater — a lazy, steady, relatively uniform downward dripping — in a slow percolation through gravel, clay and sand soils which filter and help purify the groundwater.

Given the size and interconnection of our karst groundwater recharge areas and the speed of water transport both into and through the subsurface, any water pollution and soil erosion will impact all bluff landers. Viruses, bacteria, excrement, chemicals and heavy metal concentrations can pass easily and essentially unpurified into and through our groundwater systems. Even the seemingly bright clear water flowing from a spring may include water that passed through a “wet” sinkhole used by cattle for hot-day lounging and drinking, or water that flowed through a “dry” sinkhole filled with abandoned car tires, batteries, trash and contents-no-longer-identifiable containers.

Grassed filter strips around sinkholes and along drainage rills, proper septic and sewage treatment systems, keeping sinkholes trash- and chemical-free — good neighborliness, in short — go a long way to sustaining water quality in our bluff lands. For while the greatest river of North America flows beside our lands, other rivers — hidden and subterranean — run under it.

CLIFFTOP, a local nonprofit organization, is focused on preserving and protecting area bluff lands.

A version of this article appeared in the 20 December 2013 edition of the Monroe County Independent.

© 2013 all content rights reserved Clifftop NFP

Comments are currently closed.