“Green Chaos” of Natural Landscapes or Monoculture of Invasive Plants?

Writer John Fowles spent a portion of his childhood in rural England when his family moved from a London suburb to escape World War II blitzkrieg attacks on the city. His memory of life in the country, particularly life in a setting with woodlands, was, he later wrote, “Slinking off into trees was always slinking into heaven.” The heaven Fowles sought was not a neat park-like expanse of manicured woodland. It was, as he called it, a “green chaos” of trees at all ages of growth, shrubs, vines, herbaceous flowers and grasses, and a wilderness of animals – insects, spiders, birds, amphibians, reptiles, mammals – as well as fungi, lichens and even the decaying detritus within a wooded area: the green chaos of a healthy, incredibly complex coexistence of living forms. De-poeticized scientific descriptions refer to this as “biodiversity.”

Our bluff lands still contain treasures of biodiversity – a great mix of life forms that make up healthy natural communities. While it does seem to be a chicken/egg paradox, healthy, naturally biodiverse communities are self-sustaining through biodiversity itself. An ecosystem, such as our upland oak-hickory forest, is a dynamic push-and-pull of interdependencies among and between the species that live here. The development of interdependency means that time, along with other non-biological factors, is itself a factor in the complexity of biodiversity.

Natural communities grow up together within the limits made possible by non-biological factors, including soil, weather, geology, sun and wind exposure. Co-evolution — the tendency of species within an ecosystem to become dependent upon each other – takes place over great lengths of time and through multiple generations.

Recently, our bluff lands’ natural communities have been part of an experiment in time compression. This experiment has neither a time machine under development nor, even, a white-coated, rumple-haired scientific director stirring up beakers of chemicals, admiring the arc of electric currents, or conducting various dissections and lab trials. The experiment – ongoing and underfoot on nearly every wooded and non-agricultural acre – compresses time and tests the ability of species to survive when the bounds of co-evolutionary relationships begin to unravel in quick order.

Our natural landscape is being transformed by invasive plants that alter the long-term relationships between plant and animal species, destroying wildlife habitat and our rich natural heritage.

Dennis FitzWilliam, Clifftop. This woodland, with the forest floor carpeted with wild hydrangea and other herbaceous plants, is an example of a healthy system filled with native plants.

An “invasive” plant species simply is an aggressive plant type that grows rapidly, reproduces greatly and out-competes other plant species. Within a relatively short time an invasive species can replace nearly all other plants and can even create a monoculture of only one species – itself. An “exotic, or non-native, invasive” plant species is similarly aggressive but was introduced from a distant area.

Invasive plants, including the non-native ones, grow and reproduce well in new areas due to a combination of reasons. These can include similarity in climate and growing conditions; the innate ability of the species to grow and reproduce within a wider range of conditions; an absence of predators or diseases that, in the native range, consumed either the plants or the seeds, and kept the population under control; or, the inability of the native plant species to compete, especially within the altered growing conditions that the non-native plant species itself creates. Several invasive species in our bluff lands are altering the natural plant and animal communities.

Tree-of-Heaven (Ailanthus altissima), imported from Asia to Pennsylvania as an ornamental in 1751, probably has not been purposefully planted for more than a century, but now occurs in nearly all states. A prolific seeder (up to 300,000 seeds per tree), it also spreads through numerous root suckers and re-sprouts from cut stumps and root fragments. Extremely fast growing – up to eight feet a year — once established, Tree-of-Heaven can quickly take over a site and form an impenetrable thicket. Unfortunately, Tree-of-Heaven thickets are only too numerous along the talus slope of our bluffs all along Bluff Road; even more unfortunately, Tree-of-Heaven is spreading deep into the woods.

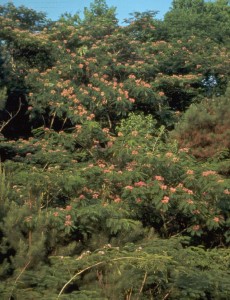

In similar fashion, Silk Tree or Mimosa (Albizia julbrissin), is a strong competitor to

native trees and shrubs in open areas and forest edges, particularly along stream banks. Widely planted as an ornamental since its introduction from Asia in 1745, and a particular favorite amongst early French settlers of our area, it spreads by both vegetative and seed reproduction. In open areas, or glades, within our woods, mimosa continues to alter the landscape, as it is a member of the Pea family, and, in common with members of this group, fixes nitrogen into the soil. The enriched soil then becomes less hospitable to native herbaceous plants that flower and re-seed best in the lean, less fertilized soils within which they evolved.

Both bush honeysuckle and Japanese (vining) honeysuckle (Lonicera mackii and L. Japonica) also were introduced as ornamental plants and sometimes still are recommended as wildlife browse, particularly for deer. But the hunter who pins hopes on these plants soon learns to curse the day he or she encouraged honeysuckle, for, while deer do eat the plants, they cannot keep up with the rampant growth. Where a healthy woodlands once nourished a variety of game and non-game species, a honeysuckle thicket soon grows and offers little food but endless tangles and noisy trip snares for humans who seek to walk through the nearly solid mass of shrubs and vines.

And, though a native of our bottomland forests, Sugar Maple (Acer saccharum) also is an invasive of our upland oak-hickory woodlands, particularly along moister north-facing slopes. Although seeds are not produced until trees are at least 22 years old, sugar maples are prolific reproducers, with the winged seeds carried up to 330 feet by wind. A Michigan study tallied 70,000 seeds per acre in the center of a clear-cut in a forest. Coupled with high average germination — up to 95% — mixed-wood forests can become dominated by maple growth.

Invasive plants can and do become the dominant species in areas where they grow without challenge. They create a monoculture of themselves and transform the landscape into a desert that gives little to no sustenance to all the species that had depended upon and which had co-evolved with the native plant community. The ability of other life forms – from morel mushrooms and lichens growing on rocks and wind-fall timber, all through insects and spiders, reptiles, birds and mammals – to live and reproduce is radically altered.

Challenging the growth and spread of invasive plant species is hard and not inexpensive work that requires a tool kit of selective practices applied over several years and, often, constant vigilance and continued work to prevent re-infestation. Landowners and managers, however, reap the rewards of helping sustain the diversity of life in our bluff lands. Beyond the beauty and the simple goodness of being part of a dynamic natural community, landowners can bank on human-centered economic returns by helping “nature” help itself.

After a bank account-filling harvest of oak and hickory timber from a woodland, ensuring correct practices so that new oaks and hickories regenerate, rather than letting the land lapse into a maple or bush honeysuckle desert, assures the landowner that children, grandchildren, even great-grandchildren, can, in turn, profit from a healthy timber harvest. And, each generation also will be able to hunt and relish the species dependent on oak acorns and hickory nuts, our deer and turkey, as well as other forest bounty, like sweet morels signaling springtime and a proper cycle of life, decay, and regeneration within the woods. And the hunters, whether for turkey, deer, or ‘shrooms, can admire a tapestry of wildflowers even as they listen to the flute-song of a thrush, the hoot of an owl, the plaintive call of a bluebird, and inhale the not-very-sweet musky scent of last night’s encounter between a fox kit and an adult skunk.

Efforts at sustaining and maintaining natural communities within our bluff lands recently have become – not easier – but, at least, a bit more affordable. When a group of local landholders formed Clifftop in 2006, the organization’s goals included improving land and wildlife management and stewardship practices and helping with the implementation of conservation programs. Clifftop has partnered with others, including federal and state agencies and additional non-governmental organizations, to help implement the Illinois Wildlife Action Plan. The genesis of this plan – recognized as one of the 10 best within the entire nation – was a 2001 U.S. Congressional effort to help reduce conservation costs throughout the U.S. by addressing wildlife habitat and species needs before critical measures (such as listing a species as threatened or endangered) were necessary.

The Illinois Wildlife Action Plan places stress on controlling and eradicating invasive plant species as a primary way of improving wildlife habitat. The partnership effort Clifftop has joined has led to a new form of conservation funding, called the Cooperative Conservation Partnership Initiative (CCPI) with USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). The entire initiative, if USDA funds remain available throughout the planned four-year extent of the program, will bring $1.5 million in funds and in-kind services to our bluff lands area for invasive species control, forest stand improvements, reforestation, prescribed burning, and conservation planning. The program will use two popular NRCS Farm Bill programs, the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) and the Wildlife Habitat Incentives Program (WHIP) and technical assistance from Clifftop, NRCS, and the partners in the local planning process of the Illinois Wildlife Action Plan, to help put quality conservation planning and practices on the land. Qualifying landowners can receive financial assistance and technical help to implement practices that benefit conservation goals.

Restoring, maintaining, and celebrating the “green chaos” of our bluff lands landscape is slinking into, indeed, hard work, but also, a bit of heaven.

Clifftop, a local nonprofit organization, is focused on preserving and protecting area bluff lands.

A version of this article appeared in the September 4 2009 edition of the Monroe County Independent.

© 2009 all content rights reserved, Clifftop NFP.

Comments are currently closed.